A messy history of LGBTQ+ dating shows

In the first of our series, Queerly Beloved: Tales of Identity and Belonging, David Opie, explores the history of LGBTQ+ dating shows From There's Something About Miriam to I Kissed A Boy (or Girl)

Reality TV should represent reality, albeit a far wilder, more interesting version, yet that's not been the case historically, especially when it comes to dating shows. Ever since ABC's The Dating Game first made us swoon in 1965, the genre has grown and grown as networks (and now streamers) far and wide dared to ask, "Can we find love on TV?" But that so-called "we" regularly failed to include the LGBTQ+ community, choosing to focus on the dating lives of straight, cisgender contestants instead.

That's the actual reality queer people have long faced, although it's baffling why you'd forego the gays if you're looking for drama. Thankfully, that's starting to change now with the introduction of new queer dating shows like The Boyfriend, I Kissed A Boy (or Girl), and even For The Love of DILFs, which all span the world in search of same-sex love. Because DILF's deserve love too.

But that's not to say queer dating shows are a new phenomenon. Rather, it's the idea of them being on equal footing to their straight equivalent that's new. When dating shows first started to acknowledge the LGBTQ+ community in the late 90s and early 2000s, it was often just as an exploitative gimmick, a modern-day freak show beamed into living rooms worldwide for the straights to laugh at and enjoy. Finding actual, genuine love for queer contestants was hardly a concern at this point, and that was even true of shows that were exclusively queer (although you could argue the straight shows aren't all that interested in real love either).

An early contender for the worst same-sex dating show ever also happens to be the first. Bravo's Boy Meets Boy was sold as a gay version of The Bachelor when it arrived in 2003, presenting the leading man, James Getzlaff, with 14 potential suitors. All were men, but what James didn't know was that half of them were actually straight. If they could deceive him and get chosen, one of these heteros could sashay stride away with $25,000.

Philip Webb, COO of the queer streamer OUTtv, says, "Every dating show has moments that make you cringe" because that's just "part of dating." But that being said, shows like Boy Meets Boy "were uncomfortable" and even "cruel". Still, young gays like me were grateful for any crumbs of representation at the time regardless. After all, seeing men date other men meant that this might be possible for me too one day. But then along came shows like A Shot at Love With Tila Tequila which almost convinced me to stop dating entirely.

While it was groundbreaking to see a bisexual Myspace (?!?) influencer land their own dating series at MTV in 2007, the show didn't just take a shot at love. It also took a shot at reinforcing harmful misconceptions around bisexuality. Female competitors in particular were horribly fetishised, and it was later revealed that Tequila wasn't even bisexual. In her words, she did the show as "gay for pay". Since then, other words Tila's also become known for include "Hitler" and "misunderstood", both in the same sentence, no less. Not quite the bisexual spokesperson we were looking for then.

It wasn't all bad though. Terrible name aside, another show on MTV around that time called Date My Mom included a few gay or lesbian episodes each season to celebrate straight parents who were actually supportive of their child's sexual orientation. Then there was NeXt, a hilariously bad (yet somehow incredible) show where contestants could shout "Next!" at any given point once they grew tired of the date they were on. A number of thirsty queers were cast over its six season run, which was pretty damn progressive for the mid noughties, although the series hasn't aged particularly well according to Dan Gray, an executive producer on BBC's "I Kissed a Boy" and its sister show, "I Kissed a Girl": "I remember laughing at the gay contestants on MTV’s NeXt. That show really wasn’t helping with stereotypes when boys jumped off the bus saying things like 'This guy better be cute and he better be packing.'“

That would be kind of iconic now. It's giving brat summer, but back then, the LGBTQ+ community was too busy fending off misconceptions and harmful stereotypes to play into what we were demonised for.

The mid noughties were a fraught time for people in the US but also the UK too. Same-sex adoption and civil partnerships had just been legalised, but many rights were yet to be won, and Section 28, the British law which prevented local authorities from discussing queerness, had only just been repealed in 2003. Amidst this climate, Big Brother UK took big strides with its first gay winner, Brian Dowling, in 2001, and then the show's first trans winner, Nadia Almada, just three years later in 2004. Proof then that reality TV could foster change on a national scale, yet that wasn't the case with dating shows still.

In fact, 2004 was the worst year yet in that regard, perhaps even the worst ever when it comes to this genre. It all started with There's Something About Miriam, a queer dating show which Love on the Spectrum co-creator Cian O'Clery would hesitate to even describe as such: "That was a morally questionable dating show in so many ways!", although the contestants didn't know it at the time. To the six men who participated, their goal was simply to seduce a woman named Miriam Rivera. But what they weren't aware of was that Miriam was trans, a fact that wouldn't be addressed until the show's very end. The finale, watched by over one million viewers on Sky, culminated with the other contestants laughing at the last remaining man on the show as Miriam's gender identity was revealed. As if that wasn't shameful enough, other scenes like the one where a doctor examined Miriam's genitalia were borderline sadistic in their cruelty, which the show and press alike took much glee in celebrating.

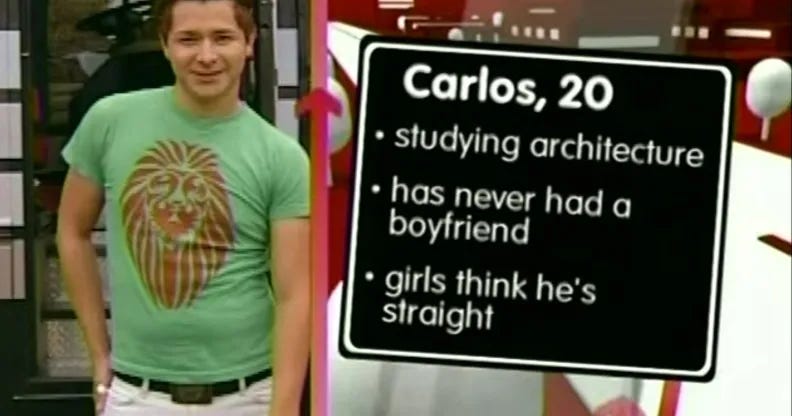

There's Something About Miriam ended after just one season, but those pining for more heartless telly were in luck when Channel 4 aired a show called Playing It Straight just two months later. There, a woman named Zoe Hardman was courted by 14 men through a series of dates and wild activities. The twist, as you can probably guess by now, is that half of them were gay. If Zoe chose a straight man at the end, they'd split a £100,000 reward, but if she chose a homosexual, then he alone would win the money. Zoe and viewers alike worked hard to "Spot the Gay," as if we're all the same, and she would quite literally rejoice when a gay contestant was eliminated. Not only did this play on harmful stereotypes — only we're allowed to do that! — it also coded the gay contestants as morally dubious people out to deceive women for monetary gain. Essentially be gay, do crime, but in the way straights perceive it. By the end, 2.3 million people tuned in to watch a gay man named Ben win because he successfully avoided coming across as "too feminine", a horrible message for straight and queer men alike.

Gimmicks like this were the bread and butter of queer dating shows back then, giving us some much-needed visibility, but rarely the good kind. "This representation rarely actually explored the reality of gay relationships," says I Kissed a Boy producer Dan Gray. "Throughout the 90s and 00s, we saw gay contributors placed into reality shows as a point of difference to be gawked at (there was typically only one allowed in a cast!) And the casting felt really repetitive (the loud gay guy to stir the pot etc.). Maybe the viewers at home weren’t quite ready for that. Camp and funny - yes please! Actually kissing each other - god no!"

"It isn’t that surprising that the mainstream has been resistant to LGBTQ+ dating shows," adds Philip Webb, COO of OUTtv. "Same-sex marriages were only legalised in 2015 in the US, 2013 in the UK and 2005 in Canada, so I think that was probably an important factor. Further to that, there is still quite a lot of open hostility to LGBTQ+ people and relationships, especially trans people, and programming decisions reflect that reality."

But as society progressed in the 2010s, so did the TV landscape. In fact, the two fed into each other, as they always do, an endless cycle where awareness and acceptance of queerness is propelled forward by media and legislation alike. With these unprecedented levels of awareness and acceptance in society came new and improved reality shows that finally started to reflect the actual reality of this world we live in.

Especially, if your reality happens to include naked body parts or blind dates with Paul O'Grady. Yes, it's true. Shows like Naked Attraction and even a new version of Blind Date started to incorporate same-sex participants into the mix around that time — and it didn't stop there either. Channel 4's First Dates had gays on as early as 2013 and then BBC Three’s Eating With My Ex followed suit with same sex couples from its first season on, starting in 2017. Then there's Married At First Sight UK, which has evolved a great deal since 2015 to include a number of notable queer pairings. And how could any of us forget Ella Morgan who became a firm fan favourite last year after she was cast as the show's first openly transgender bride?

In recent years, shows that were once exclusively straight have devoted entire new seasons to queer casting, which can only be a good thing. Take The Ultimatum: Queer Love, which asked queer couples to date new people instead of the usual straights who baulk at polyamory, even though it's what they signed up for. And that's exactly why Queer Love was so refreshing. Even monogamous queer couples are familiar enough with ethical non-monogamy to put unfounded notions of "cheating" aside. The result was a display of genuine love and respect and open communication which is practically unheard of in similar shows of this ilk. "I think a queer dating show can be more dynamic," says Gray. "You’re not bound by the two sides of a typical TV dating landscape: boys one side and girls the other. On queer shows there are so many more opportunities for connections. And friendships can also lead to romance (or vice versa) which makes things even more interesting. Plus I’m going to generalise here but I think queer people are entertaining, interesting and funny."

Eight seasons in, Are You The One? tapped into all of this by casting a whole season with sexually open contestants who could be attracted to anyone, including cisgender men or women as well as two contestants named Kai Wes and Basit, who were gender nonbinary and use they/them pronouns. In an unforgettable gender-bending queer-prom episode, Basit was empowered to debut their drag persona, Dionne Slay, in the house, while his crush Jonathan was able to explore femininity in ways he never had before. With this kind of nuance and originality in all-queer casts, it's a wonder why anyone is even asking for gay contestants to join Love Island at this point.

Alongside queer spins on established formats, the last five years have also seen a rise in gimmicky shows that exclusively feature queer contestants. Except, the gimmick is no longer at our expense. Look at the likes of For the Love of DILF's on OUTflix or Vanessa Vanjie's 24 Hours of Love, which sees Miss Vaaaaaanjie search for love in a World of Wonder sponsored house. We can actively be in on the joke now, celebrating the camp of it all while using gimmicks to our advantage in an exclusively queer space. Remember, DILF's deserve love too. But that's not to say every queer show thrives on these big concepts. Some, like BBC's I Kissed a Boy and I Kissed a Girl, are novel simply by virtue of existing.

As the first ever all-male and all-female dating shows in the UK, these two Dannii Minogue fronted milestones explore queer love with hitherto unseen honesty, mixing in chats about bottoming and sapphic joy on primetime TV amidst the genre's typical horniness — and crucially they also strive to present a range of body types, which in itself is quite unusual when muscle-bound models are usually the norm. Abs are nice to look at, sure, but in the long run, seeing abs and abs alone is more likely to inspire body dysmorphia than a hard-on. Knowing that, the largely queer team behind these shows instead cast people with all kinds of body shapes from all different backgrounds, recognising that this is what the queer community actually wants and needs moving forward. As Webb points out, "There's a big difference between a show that is about us versus a show that is for us." It's like when queer writers tell our stories as opposed to straight people trying to imagine our reality.

It's not just the UK or the US who have woken up to the appeal of queer dating shows in this vein. CTV commissioned a series called Farming for Love last year where farmers and city boys are paired off to find love in rural Canada. Naturally, plenty of milking ensued. In his native Australia, O’Clery recalls how great the Aussie version of First Dates was "when it came to representation of people you wouldn’t usually see on dating shows." The same could also be said of his own show, the original Love on the Spectrum, which defied misconceptions around neurodivergent people who are often seen as asexual or exclusively straight by people who should know better. Queer autistic participants like Journey and Dani gave a rare, much-needed voice to a marginalised subset of the LGBTQ+ community which remains almost entirely absent on screen.

Further afield, countries that don't speak English at all have also got in on the act like Spain with Who Likes My Follower?, His Man in South Korea, and most recently, The Boyfriend in Japan, bringing visibility to not just other ethnicities but entire cultures often ignored by dating shows in the UK and US (queer or otherwise). The Boyfriend is especially progressive, an adorable, wholesome juggernaut that's had gays far and wide asking, "Are Dai and Shun endgame?" "What does a chicken smoothie taste like?" And most importantly of all, why did no one try to bang Taeheon? But in truth, no one is out to bang anyone on the show. At least, not in the thirsty way we're used to seeing on screen. There is physical attraction here, of course, (I mean, have you seen them?) but the focus is on emotional connection over fake hysterics and engineered drama. Love and friendship develops organically with a sweetness that shows yet another side to the queer experience that some viewers might not be used to seeing, especially in reality TV, and even more in a country like Japan, the wealthiest democracy yet to legalise same-sex marriage.

This sobering fact reminds us that for all the progress we've made on and off telly, reality isn't where it should be still. We're a long way off from genuine equality, a world that's caught up to the truth of our lived-in experiences as queer people who just want to love and be loved as much as everyone else. But every piece of queer art that gets made matters, be it a profound epic novel or a silly dating show. If anything, it's real visibility of real queer people that can make the most impact, argues Gray, "Because seeing representation of real people (carefully done) is hugely powerful. Scripted stories are brilliant and can certainly strike a chord, but I think seeing a real person can hit differently."

And that's because we are real. We're not just the caricatures that shows like Boy Meets Boy and Playing It Straight crudely poked fun at. We too are worthy of love, even if it's a silly, camp, fleeting love made for TV.