Our revolution has always been queer & homeless

George F visits a trans-anarchist refuge in North London and explores the crowbar-toting, mascara-clad history of trans and queer housing autonomy

Historically, queer and trans people have struggled to define themselves within a patriarchal and capitalist culture, with marginal forms of identity and expression such as bisexuals and non-binary persons often having to resist minimalisation as being “not gay enough”, or “not trans enough”.

For queer squatters living under cishet capitalism, LGBTQIA+ liberation is only partially to do with sex, and everything to do with gender norms and class warfare. Our struggles are not about who we are fucking, but the systemic oppressions that are fucking us.

As Duncan Fallowell says in "Days in the Life - Voices from the English Underground 1961-1971" (1998) : “Gay Lib was nothing to do with sex, it was to do with political banners. It's even more true about the lesbian thing, which has nothing to do with the hunger of women to satisfy each other's lusts with each other's bodies - much more to do with trying to live a life in which they're not going to be eaten up by men.”

If you want peace

Stacey’s, South Tottenham

Palmed away between the chuntering workshops and converted warehouses of South Tottenham, there is a long, lean brick building painted in a stripe of flamingo pink. Along graffiti-plastered boulevards, past a mural of the trans flag overlaid with the words “OUR STREETS”, through a door fortified with car tyres, we enter Stacey’s. We are greeted by a giant nude painting of a recumbent androgynine figure in knee-high platform heels, a circled-A strategically placed over their crotch. At the door stands a mohawked punk in battle-jacket and fishnets.

The artwork is by Kat - one of the residents of Stacey’s - a transfemme-lead squat in North London that for the last four years has been a refuge and shelter to an evolving cadre of trans and queer people. Upstairs, in the organised chaos of the communal area, the afternoon sunlight streams between the pallet-barricades secured to the windows. Two dogs deliriously waltz in an otherwise serene and peaceful atmosphere. The former textile factory’s walls have been inoculated with an infusion of punk stickers, manga cartoon faces, hand painted decrees advising on the five D’s of intervening in street harassment, transliberation slogans and an urging that “NON-VIOLENCE CHANGES NOTHING”. A pile of lingerie, jeans-jackets, sweaters and socks is topped by a note that says “free to take.”

Kat, 36, and their friend Boux, 25, are recuperating after a busy morning running their dogs around Finsbury Park. The dogs are rescues. Rudy, the Belgian shepherd, was rejected by the police force, while Bruce was saved from being shot by a farmer in Wales due to his adorable overbite.

“It’s quite a lot of us at the moment. I think we are about 8 right now,” Kat explains whilst cutting the hair off of a toy doll with a pair of shears. “There's a dog. There’s two ferrets and there’s several pigeons. So it’s a refuge for us. It’s a refuge for the animals. We tried to rescue a tarantula in the early days of the squat but that didn’t work too well.”

Kat (they/them) is one of the longterm residents of the predominantly transfemme squat. “This place was intended to be a queer space to begin with. That was the vision for this squat and it kinda stayed like that. It’s difficult and not even desirable to keep a place too rigid. Right now we have someone who is a queer masc character. One of the people is not queer as far as I know. It’s transfemme lead but it’s not exclusively trans.”

Stacy’s originated as a needs-based response for trans people who needed a home. The founders fully expected to be evicted almost immediately, hence the extensive barricading, but after four years, nobody has come for them. For the community in residence, it is not only a safe space from the discrimination and disdain of wider society, but also a place to recover from addiction.

Boux (she/her) lives on a traveller site in Northamptonshire. She shares some of her experiences living there and in other squatted buildings whilst painting a new face on a doll’s head.

“The traveller site is not very inclusive. It’s very homophobic, very transphobic. They’re all in denial about it. It is quite tough when people say “I’m so glad that my kids aren’t gay or trans”. There’s an echo chamber going on that breaks when I challenge it. Alot of the younger people there get it.”

Both Boux and Kat have a history of drug and alcohol use but are currently clean and sober, in part due to their living arrangement. Boux explains how squatting and drugs are usually synonymous. “I got into squatting because that’s where the drugs were. I was homeless at the time. For me, it’s a problem that there is a generalised okayness with addiction. Almost like if you’re not an addict you don’t really belong, that you’re not cool enough, which is really toxic and dangerous. Here, it seems like people are very aware of each other’s boundaries. In other places there would be music and drugs 24/7. It’s a hotpot for crisis and very awful situations to happen. Not very much selfcare going on.”

Self care and sobriety are priorities for the Stacey’s community. Several of the residents have histories of addiction and mental health issues which the group collectively addresses through balancing a live-and-let-live antiauthoritarianism with consensual agreements such as no drugs should be used in communal areas.

Kat explains further about the politics of the space: “For me, there’s a freedom in it that you can’t find in other places - a freedom to decide how you want to live, how long for and with who. There’s more agency in squatting than there is in signing a contract with someone who is there to get as much money out of you as possible. Why would we buy into a whole market that we know is not in our favour? That we know is not helping us and never will.”

Issues of housing and addiction are particularly significant for queer and trans people, who statistically are more likely to be made homeless by their family and to misuse substances both to selfmedicate and to allow themselves to express their nonheteronormative sexuality and identity.

“In squatting, there’s this idea that we are anarchists so we just do whatever the fuck we want. This happens with drugs. If you spoke to drug-users individually they would say that they want others to feel safe and not impose their habits, but then they might use in front of others in a social setting, and take objections as a form of fascism or authoritarianism. Which is a bit fucked. Drugs become part of our lives early on as we fall out with family and find ourselves away from home. We move into squats, go to free parties, engage in sex work which can involve chemsex or other forms of drug-taking. Drugs are often tied up with queer lives but it is a complicated relationship.”

Seizing the means

The Black Cap & the Sweatpit

All squatting was unlawful, but not illegal, until the law changed in 2012 to make it a criminal offence to squat in residential properties. Currently, it is not illegal to occupy commercial properties, meaning the police will not intervene and the owner has to take the occupiers to court in order to regain possession. The transient and often chaotic nature of squatting means that the vast majority of its history is undocumented and the spaces of queer and trans people even more so.

Stacey’s is one of the more stable examples of a network of squatted commercial buildings across London and the United Kingdom that is prioritising the needs of queer and transpeople. Each intentional community is unique in its aims and culture, mirroring the needs and desires of the occupiers. Whilst Stacey’s is primarily for housing and communally supported mental health, other projects have had different objectives.

I was involved in two actions that were intent on reclaiming space as temporary nodes of resistance to heteronormativity and capitalism itself. In 2021, the former Chariot’s men’s spa in south-west London was occupied and hosted a trans and sex worker lead play party featuring an operative sauna, jacuzzi and customised container bin sporting multiple glory holes.

“The Sweatpit” - as it was known - was meant as a reclamation of queer space from the masc/gay identity of males who have sex with males that is dominant in the “hardcore gay area” of Vauxhall. It acts as a physical embodiment of the sex workers seizing the means of production and taking over the sauna.

This area of London already has a heritage from the numerous communes of the 70s that nurtured a nascent alternative culture through the squats of Bonnington Square, Vauxhall City Farm and the Women’s Liberation Movement occupations of Radnor Terrace and Rosetta Street.

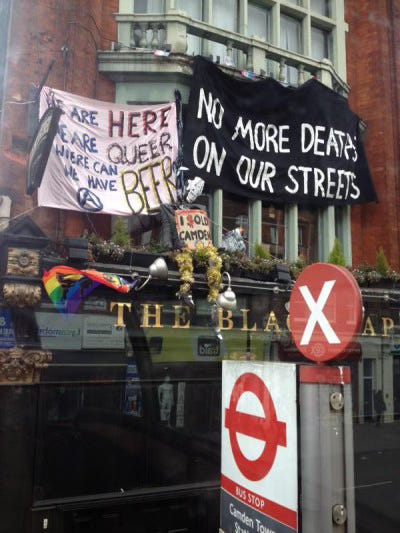

In 2015, I was part of a group known as “Camden Queerpunx 4eva” who squatted in the Black Cap in Camden only months after its closure and reopened it for a crowd of 200 people for a night of outrageous cabaret under the name “Mother Black Cap’s Revenge”. The night saw tributes to the venerable venue and was explicitly queer-lead and trans-inclusive. It was an occupation driven by the need for housing that stumbled into the frontline of defending queer space from gentrification and “yuppie gays”.

“We are the people who made Camden an international tourist destination,” my younger self claimed, “but none of us can afford Camden anymore.”

Both “The Sweatpit” and “Camden Queerpunx 4eva” were explicit examples of radical queer and trans direct action that was subsequently co-opted and that history erased by heteronormative culture. Both venues remained abandoned after these events - for nearly 9 years in the case of the Black Cap and 3 for Chariot’s - during which time they were resquatted by cishet party crews who threw raves that erased or ignored the queer-significance of the spaces.

Community is the priority

QueerWebs and cooperatives, Manchester

Outside of the capital, to the north, Manchester’s thriving queer scene has birthed a radical collective who for the last 18 months have been squatting buildings across the city under the name QueerWebs to provide safe spaces for houseless transpeople. This movement was intentionally founded in direct response to the problems of sharing squats with cishet men who had problematic behaviours.

Three months of consultation with trans people established a consensus around values of dialogue, accountability and a challenging of hierarchy. They host workshops on sexual health, polyamorous relationship dynamics and conflict resolution, and encourage a fluid and responsive methodology of cohabiting that changes to suit the needs and desires of those involved, rather than a prescriptive set of rules and expectations. During the consultations, relationships were fostered over communal meals where longtime activist and organiser Shiv, 43 (she/they), was present and deeply involved in facilitating communication and involvement with younger trans and queer people who wished to start squatting.

“There seems to be a queer uprising at the moment, a queerisation of the entire Manchester squatting scene and it’s beautiful. I’ve been squatting for over 25 years and I’ve never seen anything like it. We’re not going to erase our identity. We’re here. We’re queer. If you don’t like it, you can fuck off.”

Shiv ran away from care at 15 and joined the protest camp at Manchester airport in 1997. When that was evicted, she was taken by a bunch of punks to the 121 Railton Road social centre in Brixton, which had been originally squatted in 1972 by the legendary queer, feminist, Black nationalist squatters Olive Morris and Liz Turnbull.

“That was my first squat. It was lead by people of colour, the British Black Panther Party and the queer community. Community was the priority. Later on when I moved into squats I felt they were more isolationist, like it’s closed, it’s locked, it’s tight and in that space bad things can happen. When we are not connected with the wider community, we take our frustrations and our trauma out on each other. When you have violence from the state that’s traumatic, when you’re being evicted that’s traumatic, but when you also get violence from your comrades that is a doubling of the trauma.”

Shiv lives with osteoarthritis, and has recently moved into a queer-anarchist cooperative house with a number of people of colour and other trans people in order to have stability to manage her condition. The space is open to the wider community, including the local squatters, who come to paint banners with youth groups or use the herbalist apothecary that has been established.

“There’s a thing around being trans which is the lack of access to community, to healthcare. This is a space where we can share all our knowledge and I think that the most important thing is to be safe and to trust each other. The foundations are important. If someone comes in we have these things in place so they can feel more comfortable. I’m housed, I’m safe. We can just be together. In Manchester at the moment most of the actions and activism is queer and trans activism. That’s come from the cohesion of Queerwebs and people coming to our events and talking to each other.

“I am so happy that this is happening. There’s always been queers in squats. We’ve always found each other but the culture has always been dominated by cishet white men. I feel that there’s safe queer community. I can step back and focus on my health, on my art, on my writing and on the community. I hope that we can keep replicating this. I’m sure we can, as people are already going off and doing workshops. I’m happy for the future. A couple of years ago I slumped into anarchist melancholia. What’s the fucking point? Everyone is toxic. Now, even the behaviours of some of these cishet men are changing. They are talking and changing and owning it. We need to be gentle and allow those conversations.”

Queer housing insurrection

Shiv’s story bridges a generation of queer and trans struggle. In 1998, 121 Railton Road hosted an internationally touring festival called QUEERUPTION that took place in a different location across Europe each year. It was the heady era of anti-capitalist struggle and the anarchic festival insurrections of Reclaim The Streets and the carnivals against capitalism and the G20. These were mass uprisings born out of the punk and rave cultures that squatting had incubated, public demonstrations of optimism that promised a bright and possible future in the era of pre-9/11.

It is easy to forget, in the current climate of legalised gay marriage and a general acceptance of homosexual relationships - more than noncishet gender identities - that as recently as 1999 queer venues were the target of nail-bombings. Against this backdrop, the carnivalesque revelry of one of the biggest radical queer events for decades was captured by the image of “a biker riding a big sidecar...wearing shorts, a silver German helmet, boots and a rather attractive half-corset with circle stitched cups”.

The 121 Centre was just down the road from the site of a former radical queer space from another 20 years before. From 1974 to 1976, the South London Gay Community Centre (SLGCC) was part of a commune of squatted properties focused around its address at 78 Railton Road with an explicitly gay liberation stance, finding solidarity and shelter in the predominantly working class and person-of-colour neighbourhood of Brixton.

Ian Townson (he/him) recollects from his direct experience the various motivations queer people had for moving into squats:

“Gay people arrived at the squats for many different reasons. Some were desperately fleeing from oppressive situations in their lives. Others were glad to find the company of unashamedly out gay people rather than remain confused and isolated.

“Some consciously saw this as an opportunity to attack ‘straight’ society through adopting an alternative lifestyle that challenged the prevailing norms of the patriarchal nuclear family and private property.

“There were many visitors from overseas. Everything would be shared in common including sex partners and gender bending was encouraged to dissolve rigid categories of masculine men and feminine women. For others dressing in drag was a sheer pleasure and an opportunity for ingenious invention.

“The ‘cultural desert’ in South London offered little social space in which to gather strength as ‘out’ gay people. The ‘straight’ gay scene was inhospitable, exploitative and a commercial rip off (it is now gay-owned, exploitative and a commercial rip off).”

The SLGCC had been set up by members of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), which had exploded in the numerous squats of London in 1971, their militancy inspired by the Stonewall riot two years before. Multiple squatted houses adjacent the centre all shared a common garden where the fences were knocked down. From this nexus spawned the radical queer theatre group known as the Brixton Faeries, who paraded ‘gay dragons’ at street events and performed agitprop theatre denouncing the harm caused by the nuclear family.

Patriarchal oppression and chauvinism within the GLF clashed with a championing of autonomy and the feminist uprising, leading to vast numbers of women splitting from the communes to occupy entire streets of terraces across East London. Throughout the 70s and 80s, the neighbourhoods around London Fields and especially Broadway Market were a hotbed of militant lesbian activism. It is estimated there were over fifty women-only spaces where hundreds of lesbians lived and politically organised together, sharing lovers, childcare and housing.

Then, as now, the struggle to define a “woman” within the second wave of feminism lead to trans people striking out to form their own collectives within the freedom and agency that the abundant squatting culture provided. Bethnal Rouge, founded around 1973 in the vibrant working class east end of London, was founded “by a group of ‘radical femme acid queens’ – a group of gender-nonconformist queers, who emerged from the GLF. The Bethnal Rouge collective had to some extent evolved from the loose group of radical drag queens that had coagulated as members of the GLF, some of who had been living communally since early 1972 in various parts of London.” These were most likely persons connected with the “transvestites” who in 1971 disrupted a right-wing Christian conference by “dressing up as nuns and letting loose mice [as it was] the Bethnal Green gay commune, comprised almost entirely of transvestites, [who] were conducting this really bizarre form of street theatre.”

Directly inspired by this lineage of queer anarchism from the last century, between 2012 and 2014 queer anarchist squatters seized a string of buildings across South London to host self-managed social centres under the name House of Brag. Putting on dinners, talks and queer tango nights, they were highly critical of the London Pride event, which they saw as ‘rainbow capitalism’, and a de-radicalisation of the queer politics that challenged exploitative capitalist ideals.

The collective declared their "Monstrous Pride" would return to Pride’s "militant, intersectional roots – but with new ideas as well". A film called Brixton Fairies: Made Possible by Squatting, documenting the queer history of squatting in 1980s Brixton, was produced by one of the House of Brag residents.

Beyond squatting

The Outside Project

Squatting has been a tool of direct self-housing since the postwar era, and forms part of a continuum of short-life housing tactics that leads to the formation of cooperatives, shelters and housing security for many people. Many of the gay squats of South London became the Brixton housing co-op in the 80s, as indeed the cooperative movement across the UK has its origins in squatting.

Carla Ecola (they/them) - a former squatter - is one of the founders of the Outside Project - an LGBTIQ+ Centre and Shelter based in London. They started as a group of friends and colleagues from frontline homelessness services volunteering to run a LGBTIQ+ winter night shelter in 2017 and have been 24/7 from 2020 onwards. They also set up the UK’s first LGBTIQ+ domestic abuse refuge during covid that is now its own independent organisation - Star Support - and an outreach service in Westminster.

“Every empty building in London is fair game to be squatted. Housing is hoarded in this city like it’s a wine cellar. Squatting is just homelessness behind closed doors. As queer people, we’re just so much more limited for choice because we have to live with our own community for safety. Then if we do find a group to move in with we have high expectations of ‘queer family’ and ‘safe spaces’ having been estranged from our families and experiences of various life traumas and shame living in a cishet world. We lack the skills or capacity to support ourselves or other people finding their feet and feelings in a new town. Throw in that the majority of social space we have as a community are nightlife venues, the reality of London kicks in and it’s a pretty heavy comedown with few places to go for practical advice and support.

“I think every borough of London should have an LGBTIQ+ Centre and Shelter. Trans specific housing is a must, particularly for those who are transitioning. We need LGBTIQ+ specific housing, healthcare and hate crime support as a basic. I think anyone anywhere can set up a winter night shelter if you get the support of the local community behind you and operate on the principles of solidarity not charity.“

The queer uprising

Squats and the act of squatting is very much queer in the sense bell hooks wrote: “Queer' not as being about who you're having sex with … but 'queer' as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and that has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.” To be queer or trans was and is to be at odds with the cishet world and its systems. It is to embody a defiant challenge to the established order, to question the accepted rules and roles of gender in society in a way that squatting empty properties similarly questions the sacrosanct rights of property ownership.

Squatting may be seen as a means to an end, but in the ongoing development of radical alternatives for trans and queer people as they seek equanimity, it is more often a beginning. Like many before us, squatting has provided safety for people like myself, Kat, Boux, Shiv and Carla amidst a hostile housing environment with an uncertain future. Inside squats, cooperatives, and shelters specifically created by and for our community we have found space to heal and to become what we might dream.

For us, as for many people across the UK, the struggle for access to housing and medical care continues. For 50 years the act of squatting has provided a foundational support to our continued survival that also benefits the wider culture by questioning and diversifying the options available, normalising the once thought impossible.

George F is a queer squatter and writer. Their books Good Times In Dystopia and Total Shambles are available here.

Intereating read - it takes me back to the time when there were a lot of queer Squats in Cardiff over 10 years ago! The tension between ideological squatting (making space for comunity) and the partying and drugs was always an issue and difficult to deal with