Paradise Lost

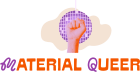

A review of Andrew Holleran's first novels; Dancer From the Dance, Nights in Aruba and The Beauty of Men

Few have examined loss with the lyricism and sensitive observation that have been hallmarks of Holleran’s novels. Larry Kramer, the author and prickly luminary of AIDS activism who died in 2020, once called him the Fitzgerald and Hemingway of gay literature, “but for one thing: He writes better than both of them.”

That’s an opinion most likely to come from a gay reader, though. Critics and publishers, often with more than a whiff of homophobia, were slow to acknowledge and appreciate chroniclers of gay life like Holleran.

Holleran is one of the greatest novelists of our time and with the re-issue of his Dancer From the Dance; Nights in Aruba; The Beauty of Men by Harper Collins, Sam Moore deep dives into the mind behind the characters.

It’s tempting to look at the first novels by Andrew Holleran, which are just about to be reissued by Harper Collins, as the kind of thing where you can call New York one of the main characters; the way people do with Sex and the City.

Across all three of these novels - Dancer From the Dance, Nights in Aruba, and The Beauty of Men - Holleran’s characters have a complex, and sometimes even combative relationship with New York; as life pulls them away from it and yet they continue to find, or force, their way back.

One of the many nameless narrators that form the chorus of Dancer From the Dance, Holleran’s debut novel, describes the circuit of New York clubs and parties on Fire Island as “the place we could not quit.” The world that’s opened to his characters often leaves a bitter aftertaste, as if they’ve been drinking from a poisoned chalice: while this is a world that exists almost exclusively for queer men - heterosexuality is only ever mentioned as an afterthought, as something for these characters to escape - it rewards a very specific, very narrow way of moving through the world.

The gates of paradise are in sight, but - as with any in-demand nightclub - you need to pay a certain toll in order to make it through the door. This tension between a promised paradise, and the reality of the characters’ lives ends up haunting Malone - the romantic, enigmatic beauty around whom the world of Dancer revolves - up until the novel’s final moments: “That was it. That was Malone—standing in the crush of voluptuous limbs, enthralled by the cold, lonely, deserted street.”

Malone is more than just a way into Dancer; he seems to be the key to unlocking this trio of novels. Each of Holleran’s protagonists carry with them aspects of Malone, with each novel echoing parts of the one before it. In Nights in Aruba, we’re told that protagonist Paul is asked when he’ll get married by his sister’s children at a Thanksgiving dinner, a conversation that Malone endures almost word for word in Dancer. And in The Beauty of Men, Lark recalls his mother saying to him “without children, life is pretty pointless,” something that Paul’s mother tells him in Nights in Aruba.

And whether each novel is a continuation of Malone’s story, or if these characters are - heaven forbid - autobiographical, isn’t even what’s important here. Instead, these details bring together Dancer, Aruba, and Beauty as taking place in a single, evolving world, one that changes with the times.

One thing that remains consistent throughout Holleran’s novels is the complex relationship that his characters have with religious faith. Holleran does more than simply equate religious faith with guilt and shame around queerness, and instead uses it as a way to understand the relationships between these men, and the worlds that they make for themselves.

In one of the most intimate moments in Dancer From the Dance, Sutherland - a seasoned queen of the circuit who takes Malone under his wing - simply reads the gospels to Malone; and the relationship between queerness and faith is further complicated in Nights in Aruba. When Paul’s mother asks if he’s gay, he insists he isn’t, all while thinking of “the scene in the Gospels in which Peter denies knowing Christ when the woman asks him if she has not seen him with the Galilean.” And while Paul goes on to acknowledge that this comparison might be out-of-proportion, he still finds a meaningful parallel between love of Christ and queer love: “if the Gospels told us one would have to leave one’s family to follow Christ, the curious thing was that loving men had the same effect. Had I not concerted my hopes from celestial to earthly ones, exchanged Christ for the boy at the baths?”

It’s no wonder then, that so many men are drawn to Malone in Dancer because of his “Christlike” eyes, or the fact that places like the Everard Baths - recurring across multiple novels - and the Fire Island pines are places in which these characters are desperate to find paradise; just as they’ve cast out their family in the same of gospels, they’re looking for something that they might call heaven.

One of the great, terrifying possibilities that dawns on Malone is essentially the same as that which came to Adam and Eve after leaving Eden: “we’re completely free and that’s the problem.” The motivations of Holleran’s dancers always feels slightly enigmatic; the reason for this dance held at arm’s length. Maybe it’s as simple as a desire to find their people, to find love; but each season sees people coming back to nightclubs like The 12th Floor, places like the Pines, as if they’re hoping to (re)discover an Eden that’s since been lost to them.

Holleran’s characters, across his novels, are drawn to this act of returning, of wondering what might be available once the past has revisited. In Nights in Aruba, Paul is constantly drawn between his life in New York, and seeing his parents in Florida, a continual echo of his mother’s belief that what’s just been passed by is the place that could have been perfect: “like the house of her dreams, the perfect motel was always the one we had just passed.”

In Dancer, Malone may have “felt he had found Paradise his first visit to Fire Island,” although as time goes by, he begins to see the place, and its rituals, as cruel. No paradise can last forever. This becomes brutally clear at the end of Dancer, when the characters gossip and whisper about the fire at the Everard Baths, and the rumours of who perished there.

Sometimes, I worry that putting queer art into its context relatively to the AIDS crisis is an oversimplification; that it continues to contort and distort everything around this one black hole. But Holleran’s novels are fascinating - and show us a world slowly fading away, never to return - because of how they chart the shadow cast by HIV/AIDS, and the death-grip it would go on to have over the community. It’s tempting to look at Dancer as uniquely utopian because it exists prior to the AIDS crisis.

As the novel’s go on, it becomes more of a reality; at the end of Nights in Aruba, “celebrities of our sexual demimonde were dying of bizarre cancers,” ending “the pleasures of promiscuous sex.” But it’s only in The Beauty of Men when the reality of this is driven home; in a flashback to 1983 the sea of a “rare cancer” is referenced, but in the mid-90s of the novel’s setting, the world of queerness has changed, has been distorted by AIDS. The throwaway reference to protagonist Lark having read And the Band Played on tells us that we’re now worlds away from the nightclubs and parties of Dancer.

Holleran closes the book on these dreams of paradise by bringing about an end to the era that represented them, and that they represented. In Beauty, he describes the passing of Sutcliffe, a queen who was emblematic of a bygone time - and someone who it’s tempting to read as a continuation of Sutherland - as being “the end of the seventies, for real.” In this moment, Holleran brings the world that so many of his characters have known and longed for, across novels, years, lovers, lifetimes, to an end.