The queer aesthetic is much more than Pride merchandise

As Pride Month approaches, when the shelves are awash with rainbows, it's easy to believe that this merchandise and apparel is 'queer aesthetic,' but really it's not.

This month, Esther McVey, dubbed the “minister for common sense,” announced plans to crack down on diversity initiatives within the civil service, including a ban on wearing rainbow lanyards.

McVey, appointed to Rishi Sunak’s cabinet as a minister without portfolio, emphasised that civil servants should leave their political views “at the building entrance” and advocated against a “random pick and mix” of causes displayed on security lanyards.

In a speech to the Centre for Policy Studies, she stated, “Lanyards should have a standard design that reflects our role as members of the government delivering for the UK citizens. We must halt the inappropriate back-door politicisation of the civil service, which diverts time and resources from focusing on the public.

“Too often, we have seen civil servants distracted by fashionable causes, particularly around issues like equality and diversity. People expect public servants to focus on improving their lives, not engage in endless internal ideological discussions. I am not prepared to see the creation of pointless jobs for the sake of political correctness.”

While McVey’s speech contains much to dissect, especially regarding what the visibility of rainbow lanyards in the workplace means for LGBTQ+ individuals, it prompts a broader question as Pride approaches next month.

Are the 'queer aesthetic' and identity deeper than rainbow merchandise?

Though well-intentioned, Pride merchandise often falls short of capturing the queer aesthetic compared to elements like mullets and cuffed trousers. However, these elements are not immune to rainbow capitalism either.

In April 2021, American Giulia Beaudoin queried her TikTok viewers on why a mirror selfie featuring green hair, wire-rimmed glasses, and black high-top Converse seemed "so much gayer" than a picture of herself in rainbow suspenders and a "Pride" hat.

“Two years ago, this was me, but it should be gayer than the other picture, yet it isn’t,” Beaudoin remarked. One comment compared the first image to attending a college and the second to wearing its merchandise. Another described the first image as an "authentic LGBTQ person in full self-expression" but the second as "giving Target Pride section." Target is akin to Home Bargains in the UK.

Monetising Rainbows

Since the first iteration of the rainbow flag was flown at the San Francisco Gay Freedom Pride Parade in 1978, rainbows have symbolised the LGBTQ+ rights movement. However, over time, Pride celebrations and the accompanying rainbow iconography have become associated more with commercialisation than liberation.

On social media, LGBTQ+ individuals often show reluctance towards rainbow merchandise, in stark contrast to the enthusiasm with which companies produce them. For example, Primark’s Pride merchandise frequently becomes the butt of jokes online.

Young adults, perhaps the most openly LGBTQ+ generation, are often disillusioned by "rainbow capitalism," a term describing how LGBTQ+ liberation is monetised and exploited for social capital. In a 2018 Vox article, Alex Abad-Santos described Pride as a "branded holiday," criticising the practice of producing rainbow products and donating a fraction of proceeds as fostering "slacktivism."

Fashion and Identity

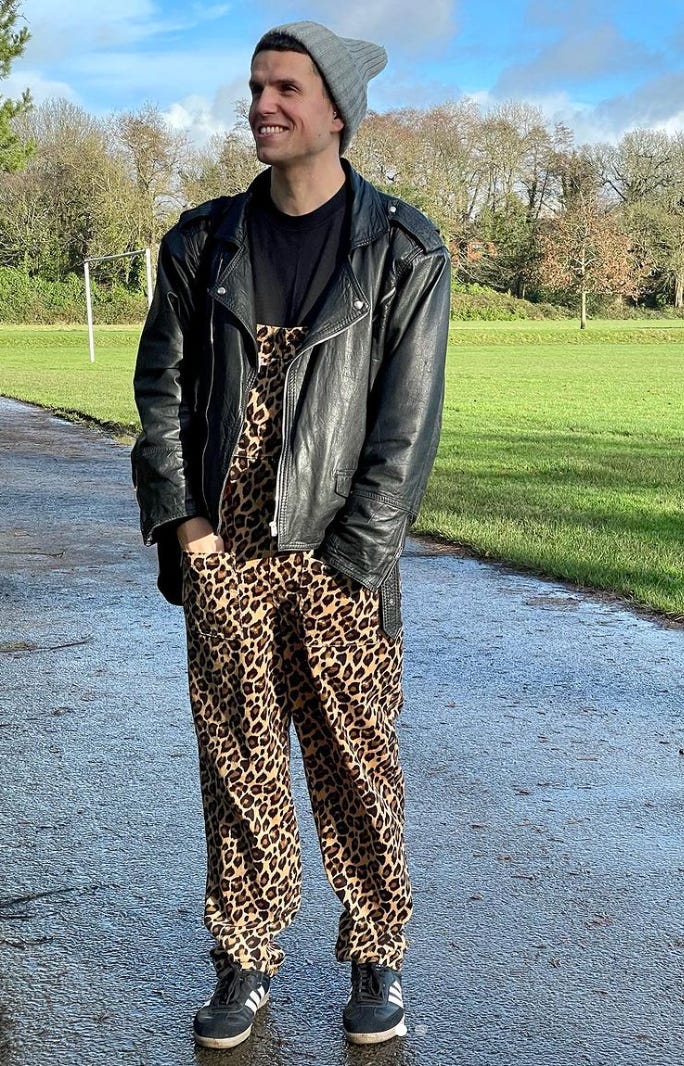

Although I love colour, as evidenced by my kitchen painted in Pantone’s 2024 colours Outré Orange and Peach Fuzz, rainbow flag merchandise or apparel has never appealed to me. My queer aesthetic features bold colours and prints, similar to how Gok Wan’s is monochrome.

I enjoy standing out and feel comfortable with my sexuality, applying lessons of self-expression from my journey with my sexuality to other aspects of life, including fashion.

While rainbow merchandise can signify someone is LGBTQ+ or an ally, other forms of gender and identity expression often feel more authentic as they were not designed specifically for gay people. The queer aesthetic is less about a defined style and more about a philosophy of presentation, veering from conventional trends to subvert social norms. This ranges from flamboyant to austere, yet each article is worn with intention, signalling subtly to other queer individuals that one belongs to their community.

Fashion as a Secret Code

Historically, LGBTQ+ individuals have used covert ways to signal community belonging. Phrases like "family," "club member," or "friend of Dorothy’s" identified someone as gay, with "gay" itself originating from a term used by female sex workers. Gay men used the "handkerchief code" to signal sexual preferences, and the carabiner has become a universal lesbian cue.

Fashion serves not only as gender-affirming expression but also as coded communication. Nobody should feel pressured to present as visibly queer. For many, it’s a matter of safety. The queer aesthetic, embraced as more authentic than the rainbow flag, faces its own commodification. Queer cues like cuffed jeans and oversized earrings can also be monetised.

Harry Styles, for instance, is hailed as a queer icon for his gender-nonconforming fashion choices, such as the Gucci gown and jacket he wore on his December 2020 Vogue cover, which sparked conservative backlash.

Public figures challenging gender norms have fostered acceptance of mixed-gendered items, making it safer for LGBTQ+ people to express themselves. While it’s important not to over-praise cishet celebrities for such fashion choices, their visibility helps normalise breaking gender binaries.

We can appreciate Styles’ fashion sense while honouring the activists who paved the way. This broader acceptance of queerness and gender diversity in fashion is not mutually exclusive.